As you probably know, a lot of my lockdown walking centred on my part of London, the north west suburbs and it is an area I will return to in more detail in future blog posts. However, during my walking, one thing that struck me was that whatever the size of the town or village now swallowed up by rapid urbanisation there was invariably prominently located a war memorial commemorating the dead of that location from both World Wars. Usually, it was a First World War memorial but with a plaque added for the Second World War and occasionally names from other conflicts too. As my walks expanded further afield and to different parts of the capital, I began to take a deeper interest in the memorials and noted that they came in several designs and styles . All of them are of course significant and highlight poignant and I will return to some of the more evocative and emotive ones in a future blog but this week, I am going to present to you perhaps the most unusual war memorials I have discovered on my travels.

- The Anti-Air War Memorial in Woodford Green

Woodford Green was a fascinating place and worthy of a further blog but undoubtedly the strangest thing there and to be honest the reason I ventured out to the far reaches of the Central Line was to see this odd memorial.

Sitting in front of a row of modern buildings somewhat hidden in the foliage is this stone bomb on a plinth. It was commissioned by the socialist suffragist Sylvia Pankhurst as a protest against air warfare. She had experienced the air bombing of London during World War One by German Zeppelin airships and also opposed British use of aerial bombardment in Burma and India in 1932 and Mussolini’s use of air power in Abyssinia in 1935. After the 1932 World Disarmament Conference decreed air bombing to be an acceptable form of warfare she commissioned Eric Benfield to sculpt an upturned bomb . At the unveiling she dedicated it to the delegates of the 1932 conference and the inscription reads: “To those who in 1932 upheld the right to use bombing aeroplanes, this monument is raised as a protest against war in the air”.

Originally it stood in front of Red Cottage, a property owned by Sylvia Pankhurst with her partner Silvio Corio, an Italian revolutionary and they wrote political leaflets in the house which also served as a tea toom. Just days after it’s unveiling the memorial was stolen and Benfield sculpted a replacement. Today Red Cottage is gone but the memorial remains albeit somewhat incongruous in its suburban surroundings.

- To the memory of Prisoners of War and Victims of Concentration Camps 1914-1945, Gladstone Park, Dollis Hill

This is probably one of the most difficult statues I have ever seen and it is very difficult to describe the emotive pull it has.

I have visited it twice and, on each occasion, I found it thought provoking while making me uneasy. I also found it extremely difficult to accurately photograph and I really recommend visiting it. Infact, Neasden and Dollis Hill surprised me in many ways and they too will feature in a future blogpost.

The sculpture is the work of Fred Kormis, born to Czech-Jewish parents in Frankfurt, Germany in 1897. A scholarship to Art School was interrupted by his drafting into the Austro-Hungarian Army at the outbreak of World War One and in 1915 he was captured by the Russians and transferred to a Siberian Prisoner of War Camp. He escaped and returned to Frankfurt but with the rise of Nazism fled to England in 1934. His major professional ambition was to produce a memorial to prisoners of war (later expanded post World War Two to include Concentration Camp victims). The five figures based on his own experiences as a prisoner reflect the sequence of figures as ‘a five-chapter novel, each chapter describing a successive state of mind of internment: stupor after going into captivity; longing for freedom; fighting against gloom; hope lost; and hope again.’ This suggests the sequence is meant to be read from left to right; the final standing figure, with arms gazed aloft and an upwards gazed, representing hope.’

Originally the intention was to place the work on a bombsite, but a suitable location could not be found and in 1967, Brent Council agreed to accept the work choosing Gladstone Park as a site with Kormis choosing the exact location in the park. As I said it is a difficult piece but I do feel it deserves to be seen be a wider audience.

- German Prisoner of War Memorial, New Southgate

The prisoner of war theme continues with my next choice in New Southgate Cemetery.

It is well maintained but difficult to read from a distance. On closer inspection you notice the names are German while the inscription reads in German HIER RUHEN IN GOTT DIE GENANNTEN/ 51 DEUTSCHEN MAENNER DIE WAEHREND DES WELTKRIEGES IN ZIVILGE FANGENSCHAFT GESTORBEN SIND [HERE REST IN GOD THESE 51 GERMAN MEN WHO DIED DURING THE WORLD WAR IN CIVILIAN IMPRISONMENT (I cannot verify why there are 53 names inscribed although William Walker doesn’t sound very German!)

These are the names of German civilians living in England in 1914 who on the outbreak of war suddenly found themselves as being regarded the enemy and the men were put into civilian internment camps. There were many all over the country not only containing civilians but also captured prisoners and downed aircrew. In London among other places Islington and Stratford had camps but by far the biggest was at Alexandra Palace and a plaque there marks this fact.

These civilians were those who died in internment for although the camps were not as tough as regular POW camps, life was still quite harsh for the internees.

On a related note, this plaque also caught my eye while meeting cruise clients at Tilbury one day.

I thought it warranted further investigation and his story is definitely one to be filmed. Now some of you will say hang on, I recall a film with Hardy Kruger about a German pilot escaping from a POW camp. That’s absolutely correct it was called “The One that Got Away” and was based on the escape exploits of a pilot named Franz von Werra who did indeed escape British custody in 1941. Von Werra though he escaped from camps in the UK was always recaptured and only succeeded in finally escaping when he was in Canada. Plüschow is the only German from either World War to have successfully escaped from Great Britain.

A pioneer of German aviation Gunter Plüschow was based in China at the outbreak of World War One. With both Britain and Japan declaring war on Germany and forces advancing on his position, Plüschow flew his plane out and reached Shanghai. With a lot of luck, he managed to get passage on a boat to San Francisco under false papers as a Swiss locksmith. However, his skill as a pilot and acquired information made him a wanted man and having crossed the United States, he learnt the British were on his tail. His false papers prevented him going to the German consulate in New York, but he managed to get passage on an Italian boat heading across the Atlantic in January 1915. Unfortunately, the boat stopped at Gibraltar where Plüschow was recognised and taken into custody. He was transferred to Donnington Hall Interment camp near Derby but didn’t remain there long. On the night of 4th July 1915, he scaled two 9ft barbed wire fences and walked 15 miles to Derby and calmly caught a train to London. Apparently, he spent time wandering the city taking tourist photos and even visited the British Museum. All this despite Scotland Yard issuing an alert to the public to be on the lookout for a man with a dragon tattoo on his arm. By chance on a bus, he overheard a conversation that a Dutch boat was departing Tilbury Docks. He made his way there and nearly drowned in quicksand trying to reach the boat but eventually made it on board and back to Germany where he was awarded the Iron Cross. After the war he made numerous trips to South America and was the first person to explore Tierra Del Fuego from the air before dying in a plane crash in Argentina in 1931.

- Civilian Tragedy Memorials

London and indeed the whole of Britain suffered greatly under air attack during both world wars and civilian casualties from air raids were substantial. There are consequently several memorials to remember this fact often at local level.

In the City of Westminster Cemetery in Hanwell is a memorial to remember civilian dead from all air raids during World War Two but there are also memorials for specific events.

In the City of Westminster Cemetery in Hanwell is a memorial to remember civilian dead from all air raids during World War Two but there are also memorials for specific events.

Perhaps the most well-known of these is the Bethnal Green Station tragedy in 1943 which although not occurring during the period of intense bombing we call “ The Blitz” (1940-41) and before the launch of the V-Weapons (1944-45) was still a period of tension with sporadic ‘hit and run raids’ by the Luftwaffe. Consequently, people still used the Underground stations as air raid shelters and on 3rd March 1943, a queue waited for the shelter to open. It is estimated about 800 people were waiting when at 8.17pm the alert sounded. At about the same time a new type of anti aircraft rocket was launched nearby and the sound confused the people entering the shelter and they surged forward. A young mother tripped at the foot of the narrow staircase and in the subsequent crush 173 people lost their lives. It was the worst civilian disaster of the war although contrary to popular belief, news of it was not supressed at the time.

Originally there was just a plaque over the narrow entrance way, the design of which was largely responsible for the tragedy.

Now there is also a more modern piece entitled “Stairway to Heaven” that was fully unveiled in December 2017 with the names of all 173 victims carved into an inverted staircase the same dimensions as the one that caused the tragedy.

There are though other civilian tragedies that are remembered in London. A little further to the east in Poplar is a memorial to the eighteen children who died when their school in Upper North Street was hit during the first daylight air-raid of World War One made by biplanes Gotha bombers on 13th June 1917. (authors note the pigeon is not part of the monument!)

The names of the children are engraved on the monument and sixteen of then are aged between four and six.

.

Fifteen of the children were buried in a mass grave at East London Cemetery while three of the children had private graves.

Perhaps saddest of all and maybe the least familiar of the memorials is south of the river in Kennington Park. In the 1930s with the threat of a conflict looming and London an obvious target, it was apparent that there would need to be some form of protection for the civilian population. One simple solution was to dig trenches in parks and open spaces and Kennington Park was one of several such systems. They were very simplistic and only intended as short term (three or four hours occupation) so the walls were lined with wood and then corrugated iron put on top. Kennington was dug as a “ladder” design (as opposed to zig-zag which would dissipate any blast wave) which proved to be a fatal flaw. On the night of 15th October 1940 at the height of a Blitz, the crowded trench took a direct hit and the blast blew people up instantly or buried them under the collapsed earth as the shockwave travelled down the trench. 48 bodies were recovered but rescuers had to eventually call off the search although it is believed the death toll was well over 100. The damaged section was covered with lime and filled in while the rest of the system was used for the rest of the war before being totally filled in 1947. The memorial which is close to the spot where the trench was hit was unveiled in 2006.

Thanks to Ruth Polling for providing this picture ©Ruth Polling 2021

- Scout Memorials

There are many municipal war memorials – post offices, train and bus stations and town halls often have memorials to workers who lost their lives either in service or at home. Factories and offices too remember their dead but two that I have discovered that are particularly worth a mention are those to Scouts.

The first is in Hanwell in Churchfield Recreation Ground and consists of two rings of horse chestnut trees surround a simple stone memorial . The plaque reads “These trees were planted by the Scouts of Ealing and Hanwell to then Glory of God and in proud memory of their Brother Scouts who fell in the Great War on 1914-1918” The second plaque reads “also in memory of the Scouts who fell in 1939-1945 war.”

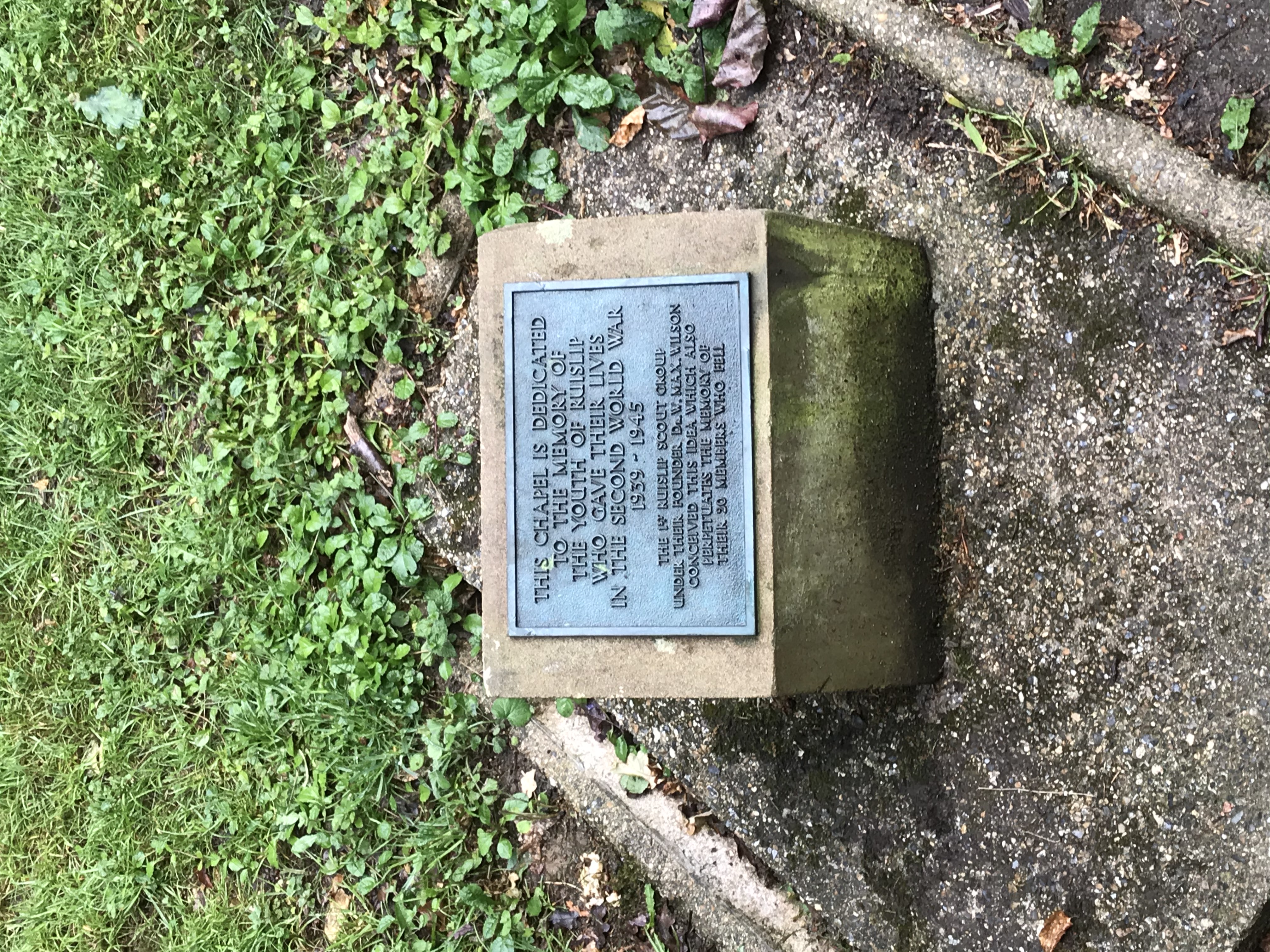

The second was a little bit harder to find and on a dry day last summer I ventured into Mad Bess Woods in Ruislip and after crashing through the undergrowth eventually stumbled on the Open-Air Chapel memorial. It is a simple open space of grass surrounded by a beech hedge with paving in the form of a cross and a small memorial.

Very simple but very effective.

There are of course hundreds of war memorials across London, this is just a small selection of the more unusual ones – all of them are accessible to the public and whoever they remember the sacrifice of those listed should not be forgotten.

Thank you for reading.

best wishes.

Steve aka The Bridgeman

All pictures ©Steven Szymanski 2021 unless otherwise specified